If you’re trying to get pregnant, you may have already compiled a list of your family's medical history to determine whether your future child is at risk for a certain disease. But there are more tools at your disposal than just a pen and paper: Your doctor can also offer a type of test called a genetic carrier screening.

This test, which can be done before you conceive or during pregnancy, can tell you if you and your partner are at risk of passing along certain genetic diseases to your children — even ones that you may not have yourself, like Tay-Sachs disease or cystic fibrosis.

It’s your choice to undergo a carrier screening, and regardless of what you decide, there's no right or wrong answer.

What is a genetic carrier screening?

A genetic carrier screening is a medical test that determines whether you or your partner is a "carrier" for certain genetic diseases and the odds that your child will inherit them.

If you're a carrier, that means your DNA contains a genetic mutation that's associated with a disease, even though you may not have the condition yourself.

If both you and your partner are carriers, and you both pass the genetic mutation along to your baby, the baby could end up with the disease.[1]

What does it mean to be a genetic carrier?

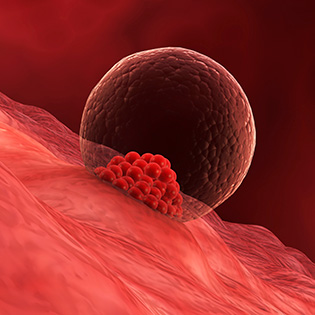

Everyone has two sets of genes: one from Mom and one from Dad. When a sperm (carrying Dad’s DNA) fertilizes an egg (containing Mom’s DNA), those two sets of DNA (which include chromosomes and genes) combine to make a new mixture — the unique genome of their baby.

A genetic disease is when a gene from one or both parents contains a mutation (a change from the usual), which could make a baby more prone to developing certain health conditions.

Read This Next

Some mutations are harmless, some only slightly boost the risk of a condition and others can cause more serious diseases or problems.

Just about everyone carries a gene for at least one genetic disorder — even if it has never shown up in a family history. If you have a mutation in one of your own two sets of genes, you’re what’s known as a carrier: You’re carrying the genes for a genetic disorder but have no signs of the disease.

Rarely, a condition (like Huntington’s disease) can be caused by a mutation in just one parent's genes. But in most cases — including cystic fibrosis and sickle cell disease — a child has to inherit one altered gene from each parent.

Who should get a carrier screening before pregnancy?

Ideally, parents will be tested for some genetic disorders before they conceive, but they can also be tested during pregnancy.

In almost all cases, testing is recommended for one parent. Testing the second parent only becomes necessary if the first tests positive.[2]

Here are the types of carrier screenings that are offered:

Carrier screenings recommended for all parents

In the past, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) only recommended carrier screenings to parents of certain ethnic or geographic backgrounds considered more at risk of specific disorders. However, some conditions are not limited to one ethnicity.

What’s more, many people are of mixed backgrounds, which means it can be hard to make recommendations based on an ethnic or geographic basis. And although they’re still very rare, some genetic conditions are common enough that practitioners should offer to screen for them in every patient.

That’s why ACOG recently released guidelines for women who are planning to have a child or are already pregnant.[3] The group now recommends that all women should get screened for cystic fibrosis and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) as well as some inheritable blood disorders, including sickle cell disease and thalassemias.

Carrier screenings recommended for at-risk parents

Because some people are more likely to carry specific genetic mutations than others, your doctor may recommend a number of other screenings based on your family heritage or medical history:

- Eastern and Central Eastern European Jewish(Ashkenazi) descent: Tay-Sachs disease, Canavan disease, familial dysautonomia and sometimes Bloom syndrome, maple syrup urine disease and Niemann-Pick disease, among others[4]

- French-Canadian or Cajun descent: Tay-Sachs disease

- Primary ovarian insufficiency: Fragile X syndrome

- Other family history of disease: Anyone who has a family history of genetic diseases — a cousin who had Tay-Sachs disease, for instance — should be screened for those diseases as well, as they’re more likely to be a carrier

Expanded carrier screening

Expanded carrier screening enables all couples, regardless of their ethnic or geographical profile, to test for a broad array of genetic conditions before conceiving.

It can screen for the carrier gene of hundreds of diseases, giving you the power of knowing whether you and your partner are at risk of passing along any of these genetic conditions to a baby you conceive together.

That said, just because the test is available does not mean couples should be screened for all the diseases out there.

ACOG has specific recommendations for which disorders practitioners should include in an expanded carrier panel. These include conditions that occur in at least 1 in 100 people, reduce the quality of life, impair cognitive or physical abilities, require surgical or medical intervention and have an onset in childhood.[5]

What are the most common genetic diseases?

Carrier screenings test for genetic diseases that have a carrier frequency of at least 1 in 100 — meaning that the mutation is present in at least 1 in every 100 people.

Here are a few of the most common genetic diseases that an expanded carrier screening can test for:

Alpha thalassemia

Alpha thalassemia is a blood disorder that causes a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin, a protein in the red blood cells that carries oxygen throughout the body. This can lead to weakness, anemia and other problems.[6]

Beta thalassemia

Beta thalassemia is another blood disease that causes a reduction in the amount of hemoglobin in the body. It can lead to anemia, fatigue, blood clots and other complications.[7]

Cystic fibrosis

This condition causes lung infections and difficulty breathing. In people with cystic fibrosis, thick, excess mucus clogs the airways and traps bacteria, which can cause infections and other complications.[8]

Familial hyperinsulinism

Familial hyperinsulinism is characterized by high levels of the hormone insulin. People with familial (or congenital) hyperinsulinism can have low blood sugar, plus more serious complications like seizures and breathing trouble.[9]

Fanconi anemia group C

This is a bone marrow disorder that causes a reduction in the number of blood cells in the body. People with Fanconi anemia experience symptoms like excessive fatigue, bleeding and bruising, and are also prone to infections.[10]

Fragile X syndrome

Fragile X syndrome is a developmental disorder in which a person lacks enough of a protein that’s important for brain development. People with Fragile X syndrome can have intellectual differences.[11]

Gaucher disease

Gaucher disease is a lipid metabolism disorder that causes too many fatty substances to build up in your spleen, liver, lungs and bones, which can keep them from functioning as they should.[12]

Glycogen storage disease type 1A

With this condition, a type of sugar (glycogen) builds up in the liver, kidneys and small intestines, which interferes with their ability to function properly.[13]

Maple syrup urine disease

This is a disease in which the body can’t process certain amino acids, leading to poor feeding, vomiting and developmental delays. It gets its name from the “sweet” smell of a baby’s urine.[14]

Niemann-Pick disease type A/B

Niemann-Pick disease type A is a disease in which an enlarged liver and spleen develop, causing growth problems, lung damage and recurrent lung infections. Niemann-Pick disease type B is less severe than type A, but is also characterized by an enlarged liver and spleen and recurrent lung infections.[15]

Sickle cell disease

Sickle cell disease encompasses a group of red blood cell disorders that affect hemoglobin. They cause your red blood cells (which are normally shaped like discs) to become crescent- or sickle-shaped, leading to anemia, or a lack of red blood cells.[16]

Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA)

SMA attacks the nerve cells in the spinal cord, causing muscle weakness and trouble with mobility and breathing.[17]

Tay-Sachs disease

Tay-Sachs disease is a type of lipid metabolism disorder that causes a build-up of fatty substances in the brain, which can lead to mental and physical problems.[18]

Again, your practitioner likely has a standard expanded carrier screening panel that’s offered to all patients, which he or she should adjust for any risks specific to you and your partner.

If you’re interested in testing for other specific diseases, talk to your practitioner about your and your partner’s risk factors, as well as how you’ll use the information about each disease. If you have further questions, a conversation with a genetic counselor can be helpful.

How can I prepare for a genetic carrier screening?

Both ACOG and the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) agree that all couples should be offered the option of carrier screening, should they choose.

A carrier screening is usually a blood test, which requires a quick prick to draw some blood from your arm. Other times, a sample of saliva or tissue from the inside of the cheek is taken. You won't need to fast or do anything special in preparation for the test.

To reduce the potential stress of receiving screening results, experts recommend that couples have a discussion with an OB/GYN or a genetic counselor beforehand to make sure they understand what’s being tested for.

This is also a good time to bring a list of any questions you may have with you. The discussion about carrier screening should also include a conversation about what you would do if these results come back positive.

Keep in mind that you can choose to opt out of any or all carrier screenings or request not to receive certain results.

When and how is genetic testing done?

Genetic carrier screening can be done when you’re just in the planning stages of starting a family, while you’re actively trying to conceive or once you’ve gotten a positive pregnancy test.

That said, if you're interested in the test, the earlier you get it done, the more likely doctors can do something if they detect that you’re carrying a mutation.

Once a sample of your blood, saliva or tissue is taken, a lab will isolate the DNA from your cells to perform the screening. Because most hospitals have to send your blood to an off-site laboratory to do carrier testing, it will likely take between one and two weeks to get your results.

How much does genetic carrier screening cost?

Genetic testing can cost a few hundred dollars or a few thousand dollars, depending in part on whether you need to test one or both partners. Health insurance will often cover the cost if your doctor recommends it.[19]

What does a positive genetic carrier test mean for our baby?

Even if both you and your partner test positive as carriers of the same genetic mutation, there’s still only a 1 in 4 (or 25 percent) chance that your baby will have the disease.

That’s because each of you has two sets of genes. Since you are carriers and don’t actually have the disease, that means you each have a second, healthy copy of the gene. If the baby inherits the healthy copy from one or both of you, he likely won’t have the disease, although he may be a carrier.[20]

A good time to get information from carrier screening is before you’re pregnant. If you and your partner do test positive as carriers of a genetic disease, you may choose to work with fertility doctors to discuss your options.

For example, technology now exists that can test the DNA of embryos created via in vitro fertilization to see whether they have a particular mutation. This is called preimplantation genetic diagnosis for mutations (or PGT-M).

A positive result may also provide a choice for you and your partner to consider sperm donation and other nontraditional routes to starting a family.

If you get a carrier screening done after you’re already pregnant, a positive result can mean more tests to see whether your baby is affected.

It could also lead to early treatments for the disease before the baby is born as well as arrangements for special care during and after birth.

And since genetic disorders do run in families, ACOG suggests that you inform relatives of positive results so they can decide whether or not they would like to be screened as well.

Also know that carrier screening still has some limitations. It can’t identify every at-risk person and there are many hundreds of diseases that doctors can’t yet test for, though the science is improving all the time.

Who should get genetic counseling?

If you have a family history of a genetic disorder such as Tay-Sachs disease or cystic fibrosis, you may want to consider genetic counseling.

Even if you don’t talk to a genetic counselor before proceeding with carrier screening, many health care practitioners will refer you to one to help you interpret your results and decide what to do with any information you obtain.

As more and more tests become available, understanding what they mean can be confusing. Genetic counselors are trained to help you sort through the available information to make sense of it.

If your results are fairly straightforward, and your obstetrician is comfortable with genetic screening, he or she may perform this counseling.

But if you’re confused about anything or want to talk through your options with someone else, it’s always your right to ask to see a genetic counselor. Most hospitals have one on staff and your insurance should cover your visit.

Genetic carrier screening is an optional test, and the choice to have it is a personal one. Ultimately, it's up to you and your partner to make an informed decision about what's best for you and your soon-to-be growing family.

Trending On What to Expect

Trending On What to Expect