Many women assume that breastfeeding will lead to a plethora of warm and fuzzy feelings as mom and baby drift off into nursing nirvana. But the reality for a small subset of women is quite different.

Imagine a scenario where awful thoughts and feelings pop up only while breastfeeding, and thoughts of mommy and me seem to disintegrate into scenes from Mommie Dearest. For some moms, this can happen, and it’s not postpartum depression. It’s a quite different condition known as dysphoric milk ejection reflex, or D-MER.

What is D-MER?

Dysphoric milk ejection reflex, or D-MER, is a condition that can affect some lactating women. It causes dysphoria, or a state of feeling unhappy, right before your breasts let down, or release, milk. It doesn’t last more than a few minutes.

While it’s most likely been around for decades, if not centuries, D-MER was first seriously investigated in 2007, when lactation consultant Alia Macrina Heise noticed she was experiencing intense negative feelings while breastfeeding her third baby.

After doing some research, she learned that other women anecdotally reported the same symptoms. But since then, there have been only a few published papers on D-MER, and even today, many physicians aren’t aware of it, despite one survey that found about 9 percent of new moms experience it. But while it’s not harmful, it can be distressing enough that you want to avoid nursing or give it up entirely.

What are the symptoms of D-MER?

Moms with D-MER describe the symptoms as coming suddenly, like a wave, a few seconds after they begin a feeding or pumping session. They experience a whole roller coaster of negative feelings such as sadness, irritation, restlessness, anger, panic and, in some cases, severe depression or anxiety.

These feelings usually disappear — as quickly as they showed up — within 10 minutes of initiating a feeding. (Some women have only mild symptoms, but for others the feelings can be severe.)

Read This Next

It’s important to remember that while these symptoms aren’t the same as the "baby blues," postpartum depression or anxiety, they can co-exist with these conditions. This is one reason why D-MER can go undiagnosed. Some women experience D-MER for only a few days, some for a few weeks or months, and some for as long as they breastfeed.

What causes D-MER?

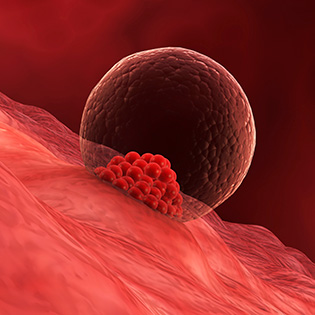

There’s no clear answer, but it’s thought to be related to two hormones, oxytocin and prolactin, that are released in response to breastfeeding. Prolactin is what causes your body to produce milk, while oxytocin causes it to "eject," or spurt out.

Oxytocin begins to be released almost immediately after your baby begins suckling — or you begin pumping — at the breast, and is released in small pulses for the first 10 minutes, while prolactin is released more gradually for about 20 minutes after you start nursing.

Once oxytocin is released, it inhibits dopamine, a brain hormone and neurotransmitter that helps boost and stabilize mood. Normally, dopamine drops properly and breastfeeding mothers never notice anything, but in women with D-MER, it drops faster than normal, which causes a brief wave of negative emotions. This is temporary, however, as your dopamine levels bounce back after your prolactin goes up.

How is D-MER diagnosed?

Unfortunately, there's no official way to diagnose D-MER. There's no blood test to see if you have it, or a screening questionnaire you can take at home or in your doctor’s office. But if your symptoms only crop up during nursing, there’s a good chance that you do have it.

How is D-MER different from postpartum depression or the "baby blues"?

Depression is common in new moms, and women with postpartum depression (and even the more short-lived "baby blues") may experience symptoms of rage, sadness, irritability and despair most of the time. D-MER symptoms occur when your milk is about to release and usually last less than two minutes, vanishing as quickly as they arrive.

You can, however, have both D-MER and postpartum depression, so if your symptoms do seem to worsen when you start nursing or pumping, speak to your physician or lactation consultant. Traditional antidepressants also seem to do little to relieve D-MER’s symptoms.

How is D-MER managed?

Since there’s very little research surrounding D-MER, it’s hard to know what the best treatment is. Happily, D-MER doesn’t last forever — most of the time, it resolves in days or weeks. Even if it persists longer than that, it will disappear once you stop nursing.

The key is to find strategies that help you cope, so that you don’t throw in the towel on breastfeeding or pumping entirely. The following steps may help:

- Surround yourself with support. With D-MER, it’s thought that breastfeeding itself triggers your body’s fight-or-flight response. In order to help turn it off, you need to put yourself in a situation where you feel safe and less stressed. This means surrounding yourself with friends and family members you trust.

- Have skin-to-skin contact with your baby while nursing. Research shows that this can lower heart rates and cortisol levels in both moms and their infants. It’s thought that if you do this while breastfeeding, you can counter the negative reaction you get during D-MER, and possibly help repair it with positive sensations.

- Practice mindfulness. Whether it’s a few deep breaths or chanting a mantra, these techniques can help you when you’re flooded with the negative symptoms of D-MER. With mindfulness, you can focus on your breathing and being in the moment. This can in turn put the uncomfortable way you’re feeling into perspective, especially if you realize that it'll go away within minutes. It can also help relieve stress, which makes symptoms of D-MER worse.

- Try to make breastfeeding as enjoyable as you can. Make yourself a designated space for breastfeeding. Have a comfortable chair and snacks and drinks there. Couple breastfeeding with a guilty pleasure, like a favorite show or fun magazines.

- Protect your well-being. If these tactics don't help with your symptoms and D-MER is taking a serious toll on you, talk to your practitioner. You may decide to stop breastfeeding, and that's okay.

In general, especially if your symptoms are mild, you may find that just being aware that you have D-MER — and that it’s a real physiological response that’s not "in your head" — can make it seem more manageable.

It’s also a good idea to track your symptoms in a log, so that you can pinpoint things that may exacerbate D-MER, like dehydration, too much caffeine, stress or even not exercising for a few days. If you have a more severe case of D-MER, ask your doctor if the antidepressant bupropion (Wellbutrin and generic) may be helpful, since it raises dopamine levels.

Trending On What to Expect

Trending On What to Expect