While your baby grows and matures over nine months of pregnancy, there’s something else growing in your uterus too — and it’s responsible for keeping your baby alive. You’ve likely already heard of the placenta, but what does it do? Here’s what you need to know about your placenta to have a healthy pregnancy.

What is the placenta?

The placenta is a pancake-shaped organ that develops in the uterus exclusively during pregnancy. It’s made up of blood vessels and provides your developing baby with nutrients, water, oxygen, antibodies against diseases and a waste removal system.

The placenta attaches to the uterine wall and connects to your baby via the umbilical cord. It also contains the same genetic material as your baby.

Your baby has just one placenta, although you may have two placentas if you’re pregnant with twins. If you have fraternal twins, each baby will have its own placenta.

With identical twins, whether you have one or two placentas depends on when the fertilized egg splits. If the placenta has already formed when the embryo splits in two, one placenta will sustain both twins, who will each have an umbilical cord linking them to the shared placenta. If the split happened earlier, you may have two placentas — one for each baby.

What does the placenta do?

The placenta is the lifeline between your baby and your own blood supply. Through all stages of pregnancy, it lets your baby eat and breathe — with your help, of course.

As your own blood flows through your uterus, the placenta seeps up nutrients, immune molecules and oxygen circulating through your system. It shuttles these across the amniotic sac, through the umbilical cord to your baby and into his blood vessels. Likewise, your baby passes carbon dioxide and other waste he doesn’t need back to you via the placenta.

More on Your Baby's Placenta

The placenta also acts as a barrier. It’s vital that germs in your body don’t make your baby sick and that your body doesn’t reject your baby as a foreign “intruder.” At the same time the placenta allows blood cells and nutrients through, it keeps most (but not all) bacteria and viruses out of the womb. It also prevents many of your baby’s cells from entering your bloodstream, where they might set off alarms.

In recent years, scientists have discovered that your placenta has even more functions than they’d known about in the past. Rather than just being a passive bridge between you and your baby, the placenta also produces hormones and signaling molecules, such as human placental lactogen (HPL), relaxin, oxytocin, progesterone and estrogen, which you both need during pregnancy.

Some of these molecules encourage new blood vessels to form — both between your body and the placenta, and between the placenta and your baby — to carry oxygen to the fetus. Some help your body prepare to make milk (but also prevent you from lactating before you give birth). Some boost your metabolism to help supply energy to both you and your growing baby.

When does the placenta form?

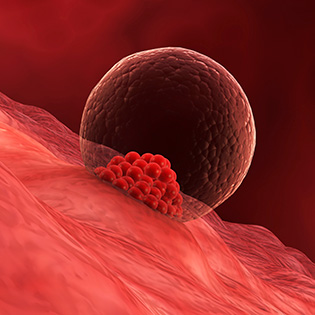

The placenta starts developing very early on in pregnancy at about week 4. Seven or eight days after a sperm fertilizes an egg, a mass of cells — the earliest form of an embryo — implants into the wall of the uterus.

Some cells from this mass split away, burrowing deeper into the uterine wall. Instead of preparing to form fingers, toes and other body parts like the rest of the embryo’s cells, these ones will form the placenta.

Over the next two months, the placenta develops. Small capillaries turn into larger vessels, providing your growing baby with more oxygen and nutrients. As you near the second trimester, the placenta will have completed its Herculean development.

When does the placenta take over?

Between weeks 10 to 12 of pregnancy, your placenta takes over from a structure known as the corpus luteum. It'll sustain your baby for the rest of pregnancy — and continue to grow larger as your baby grows.

For most of the first trimester, the corpus luteum performs the placenta’s essential functions while the organ gets up to the task. The corpus luteum is a collection of cells that produces progesterone and some estrogen. It forms every month after you ovulate in the follicle that released the egg during that cycle.

If you’re not pregnant, the corpus luteum disintegrates about 14 days after ovulation, triggering your period. When you are pregnant, the structure continues to grow and produce hormones to support your little embryo until the placenta takes over.

Forming a brand-new organ takes loads of energy and contributes significantly to first trimester pregnancy fatigue. That’s one reason you can expect to feel more energized in the second trimester, after the placenta has formed.

Where is the placenta?

In most pregnancies, the placenta is located in the upper part of the uterus. Sometimes, however, the placenta attaches lower in the uterus or on the front uterine wall (more on that in a second).

Keep in mind, the placenta is a completely separate organ from your baby formed with the sole purpose of supporting your pregnancy. It is attached to the uterine wall and connects to your baby via the umbilical cord — your baby isn’t inside the placenta.

Confused? You might be mistaking the placenta with the amniotic sac — a membrane that surrounds your baby, contains amniotic fluid and ruptures when it’s time to deliver your baby (i.e., that’s your water breaking!).

How much does a placenta weigh?

How much your placenta weighs depends on how far along you are in your pregnancy. At 10 to 12 weeks of pregnancy, the average placenta weighs nearly 2 ounces. By 18 to 20 weeks, the placenta weighs about 5 ounces.

The placenta continues to grow along with the uterus throughout the second trimester. In most women, growth slows in the third trimester as your baby maxes out the space in the womb. By the time you’re full-term, or 39 weeks pregnant, your placenta will weigh about 1.5 pounds (24 ounces).

Placental problems in pregnancy

In order to remain fully functioning and growing at the right pace, a placenta requires the same healthy lifestyle as your baby. That means smoking and using illegal drugs are off-limits.

But even if you follow every rule for a healthy pregnancy, things can go wrong with the placenta due to genetics or just chance. Other factors that can influence placental health include maternal age, high blood pressure, previous uterine surgeries such as C-sections and being pregnant with multiples.

Potential problems with the placenta include:

- Enlarged placenta, a placenta that’s grown disproportionately bigger than normal

- Anterior placenta, a placenta that’s grown on the front (anterior) side of the uterus

- Placenta previa, a placenta that covers part or all of the cervix

- Placental abruption, the early separation of the placenta from the uterine wall

- Placenta accreta, a placenta that’s attached too firmly to the uterine wall

If you experience vaginal bleeding, severe abdominal or back pain, or rapid uterine contractions when you’re not full-term, talk to your practitioner. These could signal potential placental problems.

Otherwise, your health care provider will watch for any abnormalities in the position and size of your placenta during your ultrasounds.

In most cases, placental conditions just mean that your doctor will keep an extra eye on your pregnancy since the placenta can have a wide variety of sizes and positions and still do its job.

Delivering the placenta

When you finally give birth to your baby, the last thing on your mind is likely the placenta that remains inside your uterus. But once your baby is out and the umbilical cord is cut, the placenta has no use. A new one will develop with every future pregnancy. That means after you deliver your baby, you also need to deliver the placenta (called stage three of childbirth).

You’ll continue to have contractions, and your practitioner may speed along the placenta delivery by pulling gently on the umbilical cord or massaging your uterus. What you do with the placenta is up to you and your birthing center’s policies.

While it might seem like a side thought compared to your baby, the placenta is actually an incredibly important and intricate organ that helps ensure you have a healthy pregnancy.

Trending On What to Expect

Trending On What to Expect