Not long after my daughter was born, I learned to avoid other moms. It wasn’t the best postpartum mental health strategy. Long days at home with a new baby had left me lonely, with a head full of newborn questions and Raffi lyrics, eager for adult companionship and support. I could have used a network of first-time parents who felt just as sleep-deprived and spit-upon as I was.

But whenever I did meet up with other new moms, I felt even more isolated — particularly when the conversation turned to breastfeeding, as it often did. The unspoken assumption in any group seemed to be that we were all breastfeeding. After all, we looked like good moms — educated, progressive parents who obviously wanted the best health outcomes for our little nuggets.

I felt like an imposter — an interloper in the world of research-backed practices — trafficking a half-kilo of formula in a backpack everywhere I went like a drug dealer with exclusively infant clientele. I was a closeted formula feeder, and I felt like I was constantly facing judgment for it.

It’s possible that some of this stigma was in my head. At most, I’d only heard a handful of dismayed responses when I mentioned to friends that we were relying on formula, plus a single glare of judgment from a woman in the checkout aisle that could just have easily been aimed at my beer selection.

But I’d also heard enough stories in online mom groups to know that formula had a bad rap. One poster’s anecdote in particular stuck with me. While shopping for formula, a stranger hissed at her that she shouldn’t be putting that “poison” in her child’s body. After reading her story, I felt on edge every time I checked out, and started burying the powder at the bottom of my cart like a small-town teenager hiding condoms under more innocuous snack purchases. In parenting conversations, I danced around the topic of feeding. Eventually, I simply stopped trying to connect with other moms in my small town.

Read This Next

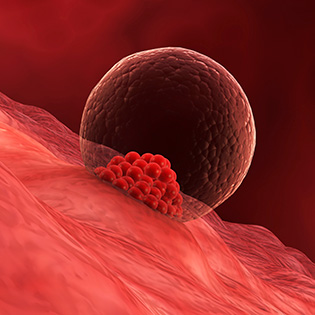

The decision to formula-feed hadn't been mine to begin with, much as I supported it. When my wife and I decided to have a baby, the presumption had always been that I would carry. But after a long, emotional year of unsuccessful fertility treatments, we had to rethink our approach.

My wife wanted a baby as much as I did, but had never planned or dreamed of being pregnant. The whole idea felt at odds with her identity as a gender non-conforming person. Like many women, she was scared of the ways that pregnancy would change her body. But breastfeeding — and the attention it would draw to her femininity — was something she dreaded even more.

Still, we wanted to be the kind of parents who follow the American Academy of Pediatrics' guidelines on everything from vaccines to the correct way to install an infant car seat to toddler screen time. Breastfeeding, with its magical pipeline of nutrition, was a big part of that plan.

But nothing ruins a good parent’s plans like the introduction of an actual child. After nine months of nausea, discomfort and feeling like her ribcage had been repurposed as a trampoline, my wife had to be induced for preeclampsia. The induction took a full two days and left her with health complications and soaring blood pressure. From day one, she tried to breastfeed but was too sick to produce a significant supply. Nearly a week later, when it was finally time to leave the hospital, frustration with her inability to nurse and sleep deprivation put her on the verge of a postpartum breakdown.

Meanwhile, I was connecting with our baby more deeply than expected — through regular bottle-feeding. This wasn’t the way it was supposed to work. As a non-gestational parent, I had emotionally prepared to be my wife’s forgotten understudy, unnoticed and unneeded until it was time for a diaper change or stroller ride. A newborn needed one thing, and I didn’t have it. The Keeper of the Boobs would be the central figure in her life until she grew old enough to notice me in the wings, waiting to teach her to ride a bike.

But armed with a bottle, I could take over nighttime feedings. Through skin-to-skin contact, I could bond with our baby and lower her stress levels. After nine months of feeling like I was making zero parenting contributions, formula-feeding promoted me to more than just a backup mom. All this helped my wife sleep better and feel less overwhelmed and alone. And I have no doubt that our nugget benefited, too — she was raised in a home with two happier and less-anxious parents, supporting each other through one of life’s hardest transitions.

Because we still believed in the magic of lactate antibodies, my wife continued to use a breast pump for four months until she had to return to her ICU job and couldn’t sustain the oddly industrial-feeling practice. After that, we stuck to formula. I now recognize we were privileged to have options. Today, my kiddo is a happy, healthy 2-year-old, completely indistinguishable on the playground from kids who have been formula-fed or breast-fed — except for the inarguable fact that she’s the cutest one.

I’ve realized that a lot of my early shame around bottle-feeding had less to do with formula itself, and more to do with my feelings of not being a “real mom” because my body had never grown a child or produced any milk. Now that I have my child care sea legs, I don’t worry about feeling less-than in conversations with other parents. Two years in, I know too much about sleep training, ear-tube surgery and the Pixar canon to worry that I’m not a real mom, whatever that might mean.

Now when I hear any disdain for different feeding styles, instead of withdrawing from the conversation I use it as a reminder to judge less and support other new moms more. We’re all out here making the best choices we can. Maybe that means breastfeeding, maybe it means using formula. As a great thinker by the name of Raffi once put it, "the more we get together the happier we’ll be."

Trending On What to Expect

Trending On What to Expect