When your doctor checks your blood pressure and asks for a urine sample at each prenatal visit, they’re partly checking for signs of a condition called preeclampsia. While pregnancy-induced high blood pressure isn’t very common, when left untreated, it can lead to potentially dangerous complications for both you and your baby.

Fortunately, as long as you’re going to your prenatal appointments, preeclampsia is almost always caught early and managed successfully. With prompt treatment, women with preeclampsia late in pregnancy have virtually the same excellent chance of having a healthy pregnancy and baby as those with normal blood pressure.

But this condition can still be dangerous for you and your baby, which is why it’s so important to know the signs of preeclampsia — and stay in touch with your OB/GYN if anything seems amiss.

What is preeclampsia?

Preeclampsia generally develops after week 20 of pregnancy[1] and is characterized by a sudden onset of high blood pressure. Around 3% to 7% of pregnant women in the U.S.[2] are diagnosed with preeclampsia, though it’s more common in Black and Hispanic women.[3]

Unmanaged preeclampsia can prevent a developing baby from getting enough blood and oxygen, as well as damage a mother's liver and kidneys — which is why it’s so important to go to all of your prenatal appointments so that your doctor can monitor you for any signs of the condition.

When preeclampsia — also known as pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) or toxemia — is diagnosed before 32 weeks of pregnancy, it’s referred to as early-onset preeclampsia.

In rare cases, untreated preeclampsia can progress to eclampsia, a much more serious condition involving seizures, or HELLP syndrome, which can lead to liver damage and other complications, and requires immediate treatment.

Read This Next

Symptoms of preeclampsia

Your practitioner should check you for the following signs of preeclampsia at every prenatal visit, but it’s still good to be aware of them yourself — and let your doctor know ASAP if you spot any of these between appointments.

- A rise in blood pressure (to 140/90 or more) if you’ve never had high blood pressure before

- Protein in the urine

- Severe swelling of your hands and face

- Severe ankle swelling (edema) that doesn’t go away

- A headache that doesn’t respond to acetaminophen (Tylenol)

- Vision changes, including blurred or double vision

- Sudden weight gain unrelated to eating

- Abdominal pain, particularly in the upper abdomen

- Rapid heartbeat

- Scant or dark urine

- Exaggerated reflex reactions

- Abnormal kidney function

- Lower levels of platelets in your blood (thrombocytopenia)

- Abnormal nausea or vomiting

- Shortness of breath caused by fluid in the lungs

Many symptoms of preeclampsia, like weight gain and edema, can be normal in a perfectly healthy pregnancy. That’s why it’s so important to regularly see your doctor, who can monitor symptoms and, if necessary, order tests to make a definitive diagnosis.

Also keep in mind that high blood pressure on its own, whether you had it before pregnancy or it developed following conception, is not preeclampsia.

What causes preeclampsia?

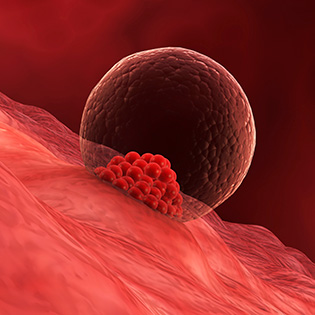

No one knows for sure what causes preeclampsia, although experts believe it begins in the placenta as your body amps up your blood production to support your growing baby.

A decreased blood supply to the placenta in some women may cause the condition to develop, and there are a number of other theories too. Some research suggests that preeclampsia may have a genetic link, and severe gum disease more than doubles the likelihood of a preeclampsia diagnosis.

Will preeclampsia affect my baby?

Preeclampsia can be dangerous for both Mom and baby, which is why it’s so important to attend your prenatal visits and get screened regularly.

One of the biggest risks for little ones is that the condition may result in a preterm delivery. Giving birth early (before week 37 of pregnancy) can increase baby’s likelihood of having a number of health problems, including trouble breathing, and might require a stay in the NICU.[4]

Preeclampsia can also up the risk of fetal growth restriction, when a baby isn’t growing as quickly as she should inside the womb.[5]

But remember that having preeclampsia doesn’t mean your baby will definitely experience these complications. And most of the time, women with preeclampsia go on to have healthy babies.

When does preeclampsia start and end?

Preeclampsia can start anytime in pregnancy, but it usually develops sometime after week 20, most often in the third trimester.

But it’s also possible to develop the condition after giving birth, which is why the Preeclampsia Foundation recommends new mothers continue to be monitored for at least the first six weeks postpartum.[6]

There isn’t a cure for preeclampsia, but it usually resolves within the first few weeksdays after giving birth, according to Jennifer Wu, M.D., an OB/GYN in New York City and member of the What to Expect Medical Review Board.

“Preeclampsia often takes up to six weeks to resolve,” says Dr. Wu, adding that some new moms need antihypertensives (blood pressure medication) during this time.

Risk factors for preeclampsia

Preeclampsia can develop in women who have no risk factors, but it’s more common in first-time pregnancies, which are generally classified as high-risk once the condition is identified.

If you were diagnosed with preeclampsia in a previous pregnancy, there’s about a 20% chance you’ll develop the condition again in a future pregnancy.[7]

This risk increases the earlier in pregnancy you were previously diagnosed, as well as if your prior diagnosis was during your first pregnancy.

Remember, you can get preeclampsia without any risks factors, but you may be more likely to be diagnosed if you have: the condition:

- A personal or family history of preeclampsia or chronic high blood pressure (hypertension)

- Pre-existing type 1 or type 2 diabetes

- Gestational hypertension

- Kidney disease

- A history of thrombophilia

- A BMI that’s over 30

- Being pregnant with multiples

- Pregnancy resulting from in vitro fertilization (IVF)

- Being very young (20 or under) or over the age of 35

- Having babies more than 10 years apart

- Autoimmune disorders including lupus

- Multiple sclerosis

- Gum disease

- Gestational diabetes

- Sickle cell disease

Preeclampsia is one of a number of pregnancy-related complications that are more likely to affect Black moms. Black women are 60% more likely to develop preeclampsia compared to white women, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[8]

How is preeclampsia diagnosed?

Regular prenatal care is the best way to catch preeclampsia in its early stages. Being aware of possible symptoms and alerting your practitioner if you notice them, especially if you have a history of hypertension before pregnancy or any other risk factors, helps your doctor diagnose the condition sooner.

Your doctor is not looking for one symptom but a pattern of symptoms. Protein in the urine, for example, is a symptom — but it doesn’t necessarily mean you have preeclampsia. And you can be diagnosed with preeclampsia even if you don’t have high levels of protein in your urine.

If your practitioner suspects you have preeclampsia, they’ll check your blood pressure, review your symptoms and may give you blood and urine tests. Your doctor will also check to see how well your blood clots and may perform an ultrasound and fetal monitoring to ensure the health of your baby.

Can taking low-dose aspirin reduce the risk of preeclampsia?

For some moms-to-be, low-dose aspirin may help reduce preeclampsia risk. In 2021, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommended low-dose aspirin for women who have a higher risk of developing preeclampsia, and this recommendation has been supported by ACOG, the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM), and the March of Dimes.

Your doctor might suggest you start low-dose aspirin sometime between week 12 and week 28 of pregnancy if you have a higher risk of developing preeclampsia or have two or more moderate risk factors, or you’re Black, even if you have no other risk factors. But because it’s not right for everyone, you shouldn’t start taking aspirin without speaking with your OB/GYN first.

Preeclampsia treatments

It’s important to get treated for preeclampsia right away to keep it from progressing to a more serious condition like eclampsia or HELLP syndrome.

While you can keep preeclampsia in check during pregnancy, the "cure" begins with delivering your baby and the placenta. Before then, treatments to manage preeclampsia depend on the severity of the condition.

For mild preeclampsia

In most cases, preeclampsia is mild, though it can progress to severe preeclampsia or eclampsia quickly if it’s not promptly diagnosed and treated.

Your doctor will probably recommend the following measures:

- Regular blood and urine tests to check platelet counts, liver enzymes, kidney function and urinary protein levels that indicate whether the condition is progressing

- A daily kick count in the third trimester

- Blood pressure monitoring

- Dietary changes, including eating less salt, more protein, veggies, fruits and low-fat dairy, and drinking at least eight glasses of water a day

- Possibly medication to lower your blood pressure (antihypertensives)

- Possibly some form of bed rest, with the goal of prolonging the pregnancy until labor and delivery is safer

- Possible initial hospitalizations to monitor the progression or stability of the symptoms, along with the possible administration of corticosteroids to help improve fetal development

- Possibly early delivery (with induction or possibly C-section) as close to 37 weeks as possible

For more severe preeclampsia

Having severe preeclampsia means your blood pressure is much higher on a more regular basis. Managing the condition helps reduce the risk of organ damage and other more serious complications.

You’ll usually be treated in the hospital, where your doctor may suggest:

- Careful fetal monitoring, including nonstress tests, ultrasounds, heart rate monitoring, assessment of fetal growth and amniotic fluid assessment

- Medication to lower your blood pressure (antihypertensives)

- The anticonvulsant medication magnesium sulfate, an electrolyte that may help prevent progression to eclampsia

- Early delivery, often once you’ve reached 34 weeks of pregnancy and your condition is stable; your doctor may give you corticosteroids to help mature your baby’s lungs to deliver her right away, regardless of gestational age

Can you prevent preeclampsia?

“There really is nothing [you can do] to prevent preeclampsia,” Dr. Wu says. But as with most pregnancy-related complications, the best way to lower your risk is to stay on top of your prenatal appointments. During these visits, you can bring up any symptoms you’re experiencing and your doctor can do a thorough exam.

These steps may also help decrease your risk — just remember that sometimes preeclampsia develops for no known reason, even if done all of the things below:

- Eating healthy. That means eating plenty of high-fiber fruits and vegetables, whole grains, low-fat protein and dairy. Good intake of magnesium, in particular, may reduce preeclampsia risk (a square of dark chocolate is a surprisingly good source). Aim to limit or avoid foods that aren’t as healthy, such as sugary or processed foods.

- Exercising. Talk to your doctor about how much exercise you should be getting; ACOG recommends 150 minutes of moderate activity (such as a walk after lunch and dinner) a week.[9]

- Watching your weight.Gaining the recommended amount of weight during pregnancy has lots of benefits for you and your baby, including reducing your risk of preeclampsia. Keep in mind that while it’s helpful to lose weight before you conceive if you’re overweight or obese, it’s never a good idea to try and lose weight during pregnancy.

- Managing chronic conditions. Chronic hypertension and diabetes are risk factors for preeclampsia, so it’s important to work with your doctor to keep these under control.

- Talking to your doctor about aspirin. Ask your OB/GYN if taking low-dose aspirin is a good option for you to lower your preeclampsia risk.

- Caring for your teeth. Some research has indicated that women with a history of periodontal disease are at increased risk of preeclampsia. So to be on the safe side, maintain good oral hygiene before and during pregnancy, which includes flossing daily and visiting your dentist every six months.

Possible complications of untreated preeclampsia

If preeclampsia isn’t treated, it can progress to eclampsia, a much more serious pregnancy condition that results in seizures and other consequences for you and your baby. Untreated preeclampsia can also lead to HELLP syndrome, which can result in complications, including liver damage.

Having preeclampsia puts you at greater risk later in life of kidney disease and heart disease, including heart attack, stroke and high blood pressure. It also increases your chances of developing preeclampsia in subsequent pregnancies.

Most cases of preeclampsia resolve at baby’s birth. Rarely, preeclampsia symptoms appear within 48 hours after delivery, although postpartum preeclampsia can happen up to six weeks following a baby’s arrival. It’s more common in those who had preeclampsia during pregnancy.

Postpartum preeclampsia symptoms are similar to those you’d experience during pregnancy (including high blood pressure and vision changes). It’s essential to let your doctor know if you notice these symptoms.

Left untreated, postpartum preeclampsia can cause many of the same complications as prenatal preeclampsia, such as progression to eclampsia and HELLP syndrome. Your doctor will likely treat you with blood pressure medications along with magnesium sulfate to prevent seizures.

Remember, as long as you’re regularly seeing your doctor, you’ll receive a prompt diagnosis and treatment — which gives you the same great odds of having a healthy pregnancy and birth as women with normal blood pressure.

Trending On What to Expect

Trending On What to Expect